During transition from late childhood to early adolescence, physical activity (participation in sports, outdoor play, and total physical activity) has been shown to facilitate neurodevelopment in the subcortical structures, the hippocampus and amygdala (as measured by an increase in their volume) in a recent study by Estévez-López et al, published in JAMA Netw Open. These subcortical regions are involved in cognitive functions (e.g., memory, decision-making, executive functioning, etc.), inhibitory control, and emotional behavior in children. This underscores the fact that physical activity is one of the environmental factors that contributes to plasticity of the hippocampus and the amygdala during childhood and must be integrated as a practical school-based intervention to promote brain health interventions for optimal neurodevelopment in children.

This 4-year-long longitudinal study analyzed data from 1008 children (mean age at baseline: 10.3 years; 52% females) from the Generation R study, a population-based cohort study, to assess the impact of physical activity during late childhood (at age 10 years) on brain development in early adolescence. The participants underwent brain morphology (bilateral amygdala and hippocampal volumes and global brain measures) measurement by magnetic resonance imaging between the ages of 10 years and 14 years. Data pertaining to level of physical activity viz., sport participation, outdoor play, and total physical activity at 10 years of age was collected from the child and the primary caregiver using an average multi-informant report.

The study results are summarized below:

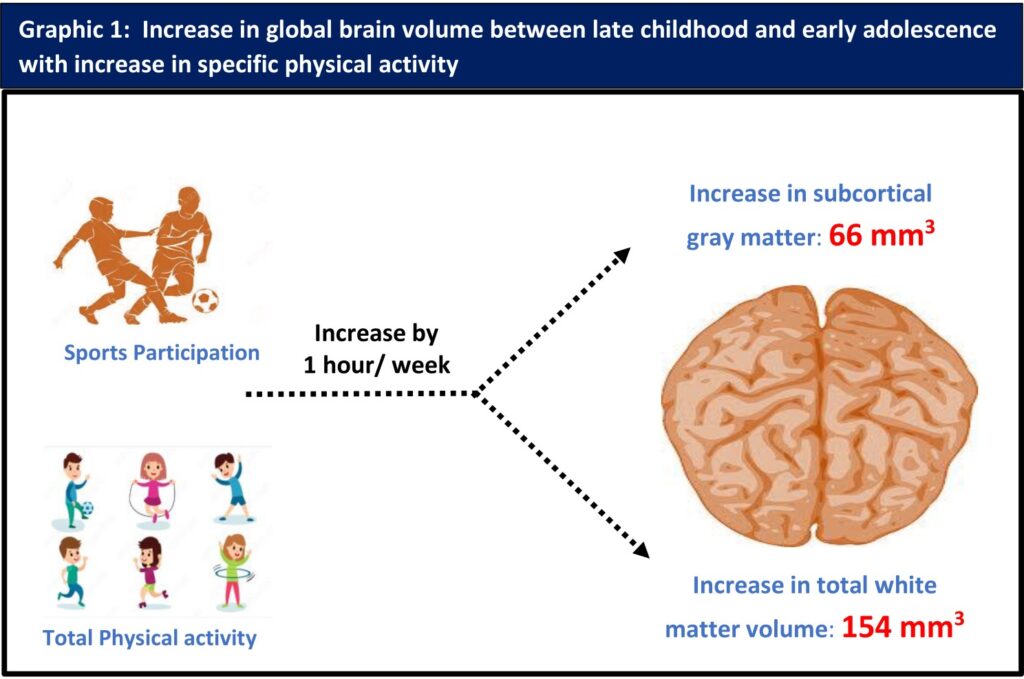

1) Physical activity and changes in global brain volume: No significant associations were reported between overall physical activity level and changes in global brain measures. However, indulging in more hours of weekly participation in sports and total physical activities at 10 years of age, as reported by the primary caregiver, was associated with specific changes in the subcortical gray (p = 0.04) and total white matter (p = 0.02) volumes of the brain (Graphic 1).

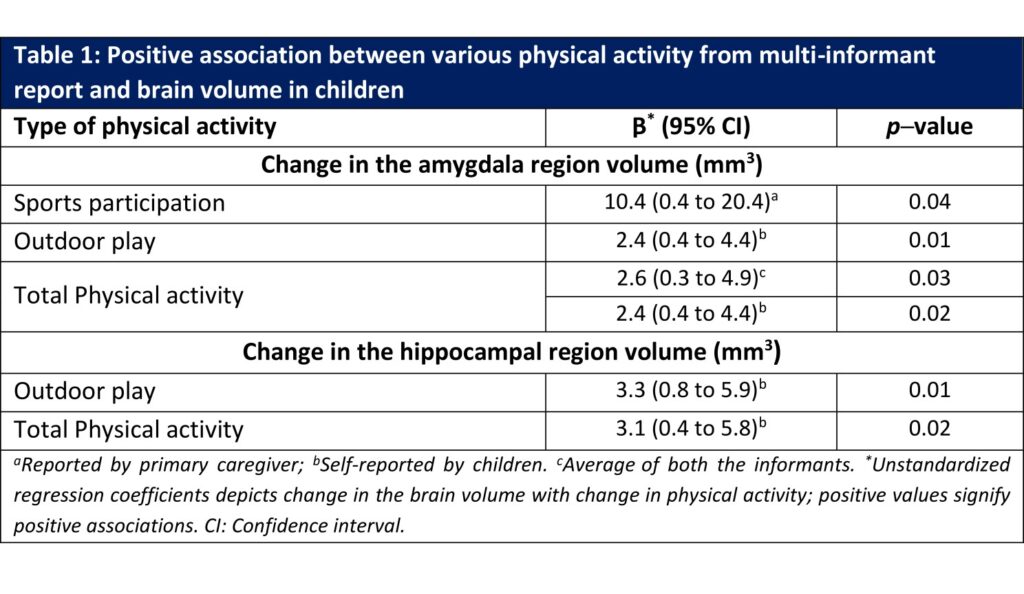

2) Physical activity and changes in the amygdala region: Total physical activity during late childhood was linked with an increase in the amygdala volume during early adolescence (14 years) across both the informants (p = 0.03; Table 1). Active sports participation reported by primary caregiver (p = 0.04) and outdoor play engagement reported by the child (p = 0.01) were positively associated with increase in the volume of amygdala (Table 1).

3) Physical activity and changes in the hippocampal region: Physical activity as well as outdoor play were not associated with changes in hippocampal volume, except when self-reported by the child (Table 1).

Clinical implications

1) This study highlights the positive impact of physical activity on the brain development in children. Encouraging children to participate in increased physical activity during late childhood may contribute to improved cognition, emotional behavior, and learning during transition to early adolescence.

2) These results can guide the development of future physical activity interventions through public health and school-based programs to enhance optimal neurodevelopment in children.

(Reference: Estévez-López F, Dall’Aglio L, Rodriguez-Ayllon M, et al. Levels of physical activity at age 10 years and brain morphology changes from ages 10 to 14 years. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(10):e2333157. Doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.33157)